I feel called to be here. I do this work on behalf of the loved ones I’ve lost and the ones who are living. I do it for the next generation of activists. I do it for people I’m inspired by and whom I look to as my heroes. I want to continue to be of service, and to be hopeful and loving and kind. Being kind is incredibly important, especially now.

Krishna Stone

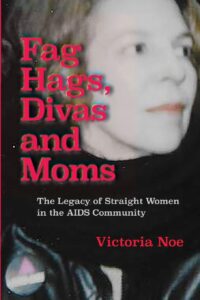

When HIV activist and author Victoria Noe couldn’t find a single book that told the stories of straight women fighting the AIDS epidemic, she decided to write it herself. That led her to GMHC Community Relations Director Krishna Stone, who started working for the agency in the epidemic’s early days, when gay white men were leading the charge.

“There is a wealth of work and service around HIV and AIDS that continues to be done by straight women, so it was lovely that someone thought to ask about that,” says Stone, a straight Black woman. Noe interviewed Stone for her 2019 book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community, and then for the sequel coming out in September: Unstoppable: Straight Women on the AIDS Frontlines.

“There is a wealth of work and service around HIV and AIDS that continues to be done by straight women, so it was lovely that someone thought to ask about that,” says Stone, a straight Black woman. Noe interviewed Stone for her 2019 book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community, and then for the sequel coming out in September: Unstoppable: Straight Women on the AIDS Frontlines.

Stone says that when she talked with Noe for Fag Hags, Divas and Moms, she felt comfortable owning all three roles. “I felt inspired talking to Viki about who I am and the work that I do, as a straight woman, a mom, and a fag hag – because I was. I’m not ashamed of that at all. I continue to be a mom and of service, and maybe a diva. I like to refer to myself as high maintenance.”

A lover of Disco Classics, Stone arrived in New York City at age 18 to attend New York University, just as the 1980s were getting underway and the city was soon to become the epicenter of the AIDS crisis. She immersed herself in the vibrant Disco club scene, particularly the gay clubs, she says, because they had the best music.

As her friends and colleagues started dying, Stone walked for the first-ever AIDS Walk New York in 1986. That inspired her to start volunteering for Gay Men’s Health Crisis, launched in 1982 as the world’s first AIDS service organization. Stone joined GMHC full-time in 1993 in the Volunteer Department, then became Director of Community Relations in 2003.

One of her proudest moments was serving as a Grand Marshal for the NYC Pride March in 2017. “It was one of the most extraordinary days of my life. I was being honored for my work, my service, who I am in the community as a straight ally. It was brilliant,” says Stone, who memorialized the moment with a Grand Marshal tattoo.

Noe and Stone will be discussing Unstoppable: Straight Women on the AIDS Frontlines on Sunday, Sept. 14 from 3:00–4:30 pm at the LGBT Community Center at 208 West 13th Street. The event is free and open to all.

The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

GMHC: Most of the straight women in Noe’s book got involved in HIV and AIDS work in the 1980s and 1990s, because they had a gay friend or family member who was affected. Your story is a little bit different. Why did you get involved?

Krishna Stone: I don’t know if you’ve ever been somewhere when you hear there’s a hurricane coming. It gets really quiet, then the wind picks up, and the rain. That’s how I felt, understanding something was about to happen. There’s a Roberta Flack song, “Uh-Uh Ooh-Ooh Look Out (Here It Comes),” that starts out saying “Something’s wrong.” That’s what it was like.

I came to New York for college at a divine time. I love Disco Classics, and this body of music was exploding at the dance clubs. The clubs were exquisite at that time – the music was stunning and beautiful. But as the early years of the 80s went on, I would go to a club and someone who worked there – a waiter, DJ, or bartender – had disappeared. People were dying of AIDS-related complications. One day they were here. Another day they were gone. When I’d go to the Paradise Garage, I’d ask myself who I was dancing for that evening – like I was holding my own memorial service.

One of the loves of my life, Max, was a waiter at the Ice Palace on 57th Street. He was magnificent. We broke up when he started having sex with men, and then reconnected years later at GMHC, where he’d become a client. He made it through the 1980s and 1990s, then went into hospice care at Calvary Hospital in the Bronx. My last conversations with him were on the phone – and then he was gone. A couple of my other friends also died there.

Through those early years, I was visiting friends at their homes or hospitals, including St. Vincent’s Hospital, which was on the front lines for the epidemic. I don’t know how many friends I lost. I also was losing friends from breast cancer.

Did the stigma around AIDS or being LGBTQ+ affect you in those early years, working for GMHC?

At times, I’d mention working at Gay Men’s Health Crisis to someone and get a blank stare. For me, it was a teachable moment. It was really our clients and some staff who were affected. They were experiencing stigma, isolation, and abandonment from family members.

I went to a lot of funerals and memorial services, and the programs would say nothing about who these men were. That they were gay men who died of AIDS-related complications. That they sang in the NYC Gay Men’s Chorus. Anything gay was taken out. I was livid over one for a brilliant psychologist friend and colleague, a Black gay man. It mentioned nothing about him working for GMHC or being gay. I was so upset, that I left the service and walked for blocks, from 120th to 80th Street.

When women started coming through the door, particularly if they were mothers, they felt the stigma. GMHC started a child-life program with a playroom, because parents wanted to bring their children while accessing services. What was also very heartbreaking were the children who didn’t know their parents were HIV positive, because their parents didn’t want them to be stigmatized. Bullies can be brutal.

It was – and still very much is – a part of our work to support people moving through stigma, whether it’s transphobia, homophobia, or living with HIV as a straight woman. In every capacity that clients connect with our services, whether supportive housing, counseling, or meals, we are working with them in a holistic way to move on and thrive.

Earlier on, GMHC had a reputation as being mostly white, gay men. As a straight woman of color, what was that like?

I felt at home working for GMHC. My friends were mostly gay men, along with lesbians, transgender, and straight people. I knew a lot of them from my jobs in restaurants and theater, doing comedy improv. And then I became a parent, so my circles were very intersectional as a mom, a straight ally, a diva – the High Empress of Disco Classics — and a volunteer.

The folks at GMHC gave me a massive baby shower before Parade was born in 1995. It felt like everybody was rooting for this baby. Parade arrived a week early, so when I was in between contractions my supervisor, David, came by to be briefed on a citywide conference I was organizing for people volunteering in hospital settings and HIV/AIDS service organizations. There weren’t that many straight women at GMHC then, but through the 1990s, more cis and transgender women and people of color started to get involved, both as staff and volunteers.

How have the demographics and needs of GMHC’s clients changed over the years?

Their needs have expanded. We serve New Yorkers from all five boroughs, and over 70% live below the federal poverty line. Just over two-thirds are LGBTQ+ and about half are living with HIV. Now, almost two-thirds of the agency’s clients are Black or Latinx, and about one-fifth are women. These kinds of complex, multilayered experiences have been exacerbated by all that’s going on in the world, from COVID-19 to the wars, and immigration crackdowns.

You have a real talent and dedication for connecting people. How does that play out in your role as Director of Community Relations?

My work is about fostering new partnerships and nurturing old partnerships. These can be with our supporters, media, or around community events. For example, I’ve served on planning committees for citywide World AIDS Day events and liaised with NYC media on GMHC news. I often do presentations about GMHC for companies that want to learn about what we do, and they frequently ask me to share guidance with their employee groups on what it means to be a straight ally.

Our supporters are diverse and wide-ranging, from corporations to the Broadway theater, media, and restaurant industries to faith communities and colleges. We also partner with government and social service agencies like the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, other HIV and AIDS service organizations, and LGBTQ+ and youth nonprofits. And we work with local and state elected officials and their staff. These partnerships are more essential than ever right now. In this time, we really have to stick together.

You’ve worked at GMHC for 32 years and counting. What has kept you here so long?

I feel called to be here. I do this work on behalf of the loved ones I’ve lost and the ones who are living. I do it for the next generation of activists. I do it for people I’m inspired by and whom I look to as my heroes. I want to continue to be of service, and to be hopeful and loving and kind. Being kind is incredibly important, especially now.

Stay in the Know

Sign up to receive our monthly newsletter, updates about events, and other helpful information.